The White Princess

- Jacob Lyngsøe

- May 12, 2020

- 7 min read

Updated: Jan 20, 2024

In the sparsely documented realm of cruising history there is no shortage of ships claiming the title of world’s first cruise ship for one reason or another, but if we look for the first purpose-built luxury cruise ship, designed exclusively for cruising, there is only really one candidate: the Prinzessin Victoria Luise – the White Princess. Unfortunately, unlike many other princesses, she did not get to live happily ever after.

Wednesday, 16 December, 1906 - 09:30pm

Off Kingston Harbor, Jamaica: The sudden and violent impact throws everyone off their feet; bridge officers tumble to the deck, cruise guests are thrown awake or out of bed, card games are upended and soirées brutally interrupted as guests and crew are tossed forcefully against the bulkheads. Lights flicker, sirens blare, metal groans, decks tremble briefly. Seconds later Captain Brunswig storms onto the bridge and demands a situation report from the officer of the watch. He does not need anyone to tell him the ship has run aground but he desperately wants to know why, where and how badly. Outside the bridge windows, the inky black Jamaican night offers no clue to what just happened. The damage reports start to come in; Flooding, multiple compartments, port side forward. Main engines dislodged, multiple fuel and hydraulic leaks. The only good news seems to be that there are no casualties reported and that whatever they are stranded on, it is large and stable enough that the ship will not sink. Unable to conduct a safe evacuation at night or call for help, passengers and crew spend an uneasy night on the grounded vessel.

Daybreak confirms what sextant readings have already indicated – the ship is nowhere near where it was supposed to be. During the evening Captain Brunswig mistook the lighthouse at Plumb Point for that at the westernmost point of Port Royal, so instead of plotting a safe course through the channel out of Kingston bay, he ran her squarely aground on the Palisadoes isthmus (where Norman Manley Int’l airport is today). Captain Brunswig holds a final crisis meeting with his senior officers and orders the evacuation of all passengers and crew to the nearby shore. As the last boats depart, he makes his way across the slanting deck back to his cabin. He opens his wardrobe closet, pulls out a rifle and shoots himself dead because that is how a proud career captain dealt with humiliating failure in those days.

Three days later, after authorities have given up all attempts to tow the stricken ship off the bottom and a passing storm has beaten even more structural integrity out of her, the Prinzessin Victoria Luise is declared a total loss. That was the dramatic and tragic end of the world’s first purpose-built luxury cruise ship. Her beginnings – while less dramatic – are equally interesting.

Seven years earlier

Hamburg, Germany: In late 1899, the 43-year old Albert Ballin becomes general director of the Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Actien-Gesellschaft (HAPAG) or Hamburg-America Line. Ballin was the one who brought HAPAG into cruising – frustrated at seeing the company’s finest ocean liners laid up (and unprofitable) every winter when the Atlantic became too rough to cross, he introduced luxury cruising in 1891 as a way to monetize the tonnage in off season (read Ballin's Gamble). This was an unqualified success and exotic luxury cruising in winter season became a regular activity for HAPAG, and soon the competition too. Great as the idea was, it was still not ideal – certain handicaps became apparent as ocean liners started donning the mantle of luxury cruise ships.

Firstly, the class division of ocean liners into first, second and steerage made them uneconomical to operate as cruise ships. To operate luxury cruises, you could only sell first class cabins and they were typically the smallest category of cabins onboard. Yet you still had to operate an entire ship of 4-5 times that passenger capacity. That seemed, at best, wasteful.

Secondly, the fuel consumption was equally wasteful. The powerful engines of ocean liners were built for a full-speed sprint across vast oceans, not for puttering leisurely around coastlines and archipelagos. Fuel consumption was atrocious at slow speeds, greatly increasing the cost of doing cruise business.

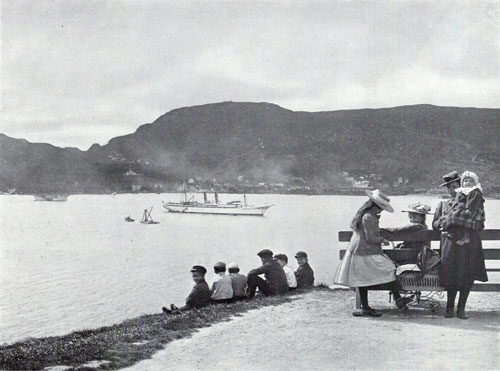

The Prinzessin Victoria Luise in a Norwegian Fjords Summer Season

Thirdly, the ocean liners were built for the cool, rough North Atlantic and lacked the kind of open deck spaces you would want in warm, tropical waters. Deck space on the liners tended to be covered, cluttered and class-divided and not suitable for much outdoor activity.

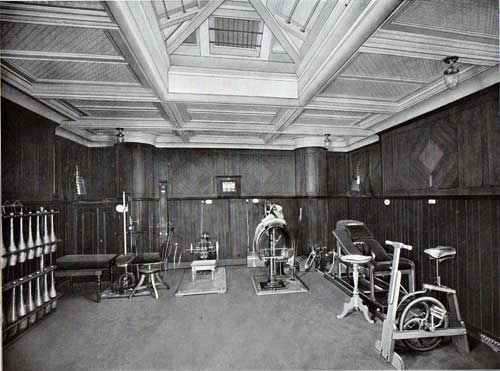

Finally, the ocean liners did not really offer much diversion or leisure facilities onboard. A Transatlantic crossing in 1900 took around 6 days (Liverpool – New York) and the ships were neither designed nor expected to keep people entertained for any longer than that. But the new ‘luxury cruises’ could take several weeks, if not months. A dining room and a couple of social lounges were no longer going to cut it for guest activities.

A purpose-built luxury cruise ship

Ballin acknowledged these conceptual flaws and decided the best way around it would be to construct a new type of ship; one that was designed and engineered as a full-time luxury cruise ship. A few months after his ascension to general director he commissioned the Blohm & Voss shipyard to construct such a ship, to be named after the Emperor Wilhelm II’s daughter, the Princess Victoria Luise.

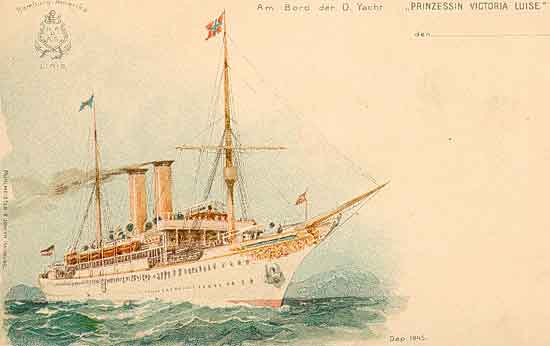

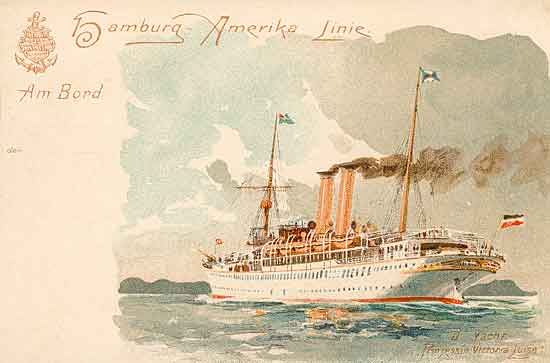

Vintage Postcard, Prinzessin Victoria Luise, Cruiselinehistory.com

In keeping with her name and to attract the right breed of high society clientele, she was modelled on the Royal Yachts of Europe, exuding class, elegance and luxury from every angle. She had a trim clipper hull, sleek curved lines between a richly decorated bow (complete with bowsprit) and a stylish counter stern and two slim and rakish funnels in buff color amidships between twin masts. She was one of the finest examples of the ‘yacht aesthetic’ that would characterize the first generation of purpose-built cruise ships in the early 20th century. In a break from tradition she was given a coat of snow-white paint – a choice that served the practical purpose of helping to cool the hull in tropical climates but would end up becoming synonymous with cruise vessels.

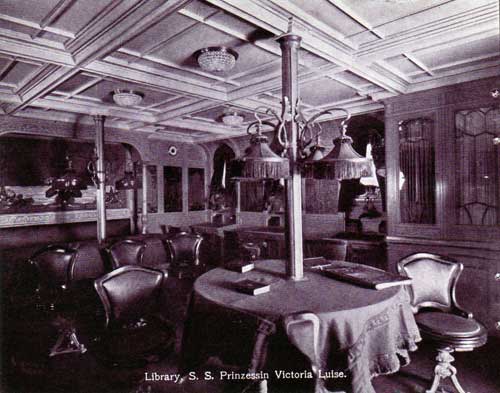

At 124m / 407.5ft length, 14m / 46ft beam and 4.409 GRT weight, she was barely even half the size of her contemporary ocean liner cousins but that only made her more cost-effective and deployable. The class divisions were gone – all 120 cabins (180 pax maximum) and public facilities were first class and 161 crew members guaranteed a high service level. Modern quadruple expansion steam engines ensured a sound fuel efficiency and the decks were spacious, uncluttered and ideal for sightseeing and promenades. In addition to the traditional features of dining room, smoking lounge, music salon and ladies’ parlor, guests could now also pass the time in a well-stocked library, work out in the onboard gymnasium or develop photographs in the onboard dark room (the latter two possibly the first of their kind at sea).

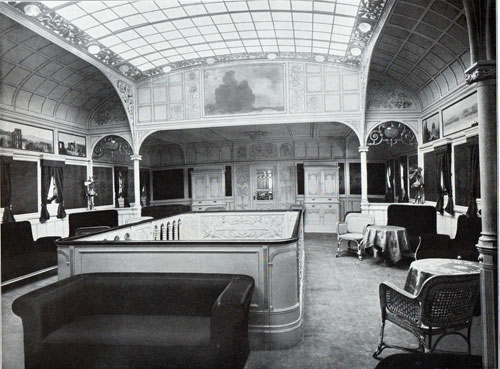

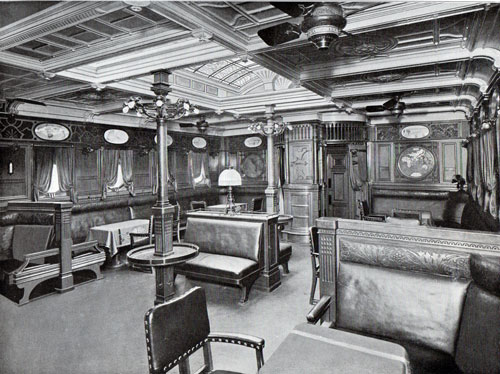

Interiors public areas, Prinzessin Victoria Louise - slideshow

Setting new standards

The interior design and appointment were a continuation of the ‘floating hotel’ philosophy Ballin had introduced to HAPAG – the luxury, quality, service and experience of a five-star luxury hotel, but at sea. Spacious salons topped with crystal-paned domes and lavish lounges with plush furniture and carpets in rich colors, decorative plants and fresh flower arrangements everywhere plus stylish art nouveau decoration and gilded detail work on every wall. A central 3-deck light shaft between the glass-domed social hall and the main deck dining room was the forerunner to the ‘atrium’ feature that would find universal use on cruise ships some 70 years later. From stem to stern she was not only beautiful, but practical and ideally designed for her purpose in life.

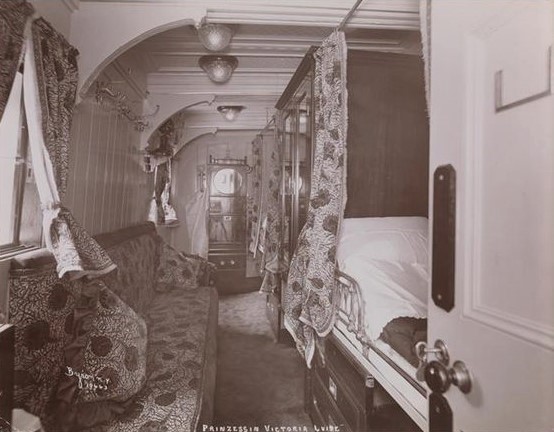

The accommodations were also of an unprecedented new standard of opulence; spacious, luxuriously appointed staterooms with beds in side-by-side configuration rather than bunk beds, electric lights and a fan for ventilation as well as an electrical paging system for the steward. Two sinks with running water in each cabin enabled some basic hygiene, but for a proper bath you would still have to befriend the ‘bath steward’ who ran the bath roster for the communal bath rooms (unless you were in the Emperor’s Suite – that one did have a bath tub).

Cabin interiors Prinzessin Victoria Luise - slideshow

All in all, Ballin had taken his decade worth of practical experience with the operation of luxury cruises, distilled it, honed it, poured it into a classically beautiful vessel and topped it off with first-class service, superb cuisine and meticulous organization - it was truly a ship (and an experience) ahead of her time. The Prinzessin Victoria Luise overcame all the shortcomings of the ‘ocean liners as cruise ships’ trend and signaled the arrival of the purpose-built cruise ship in the shipping industry. Not only would she go on to prove that there was a market for full-time, designated luxury cruise ships but she created new standards and trends for all of her successors and set off a trend of cruise ship newbuilds in the same mould. Almost 60 years into the history of cruising, the cruise phenomenon had finally found its unique and lasting form – the ‘cruise ship’ was now its own entity, separate and apart from ocean liners.

The Prinzessin Victoria Luise set off on her maiden voyage from Hamburg on 5 January, 1901 and sailed directly into the hearts of European and American high society of the 1900’s. She quickly gained a loyal following of repeat guests, sailed all over the world and turned heads wherever she went … until that fateful night in December 1906.

Epilogue: Back near Kingston

As the wrecked Prinzessin Victoria Luise was sitting forlornly on the Palisadoes isthmus, a number of snow-white reefer ships passed her regularly going in and out of Kingston, their upper decks crowded with cruise guests gawking at the beached princess, and their holds crammed with bananas. Those were the ships of the United Fruit Company – the grandfather of Caribbean cruise dynasties. But that’s an entirely different story, found elsewhere in the pages of cruise history.

This is the eighth article in a series of historical retrospectives on the history of cruising prior to the industry formation in the 1960's. Although not academic papers, the articles are researched to the extent of my resources and ability and strive to be as historically factual as possible. If you enjoyed it, feel free to like, share or comment and follow me (or The Cruise Insider) for more instalments.

Comments